When is a Casting Returnable?

Nearly every casting has an irregularity. While most don’t cause a part to fall out of specification, some can be significant enough to send the casting back to the foundry.

Metalcasting is a modern manufacturing industry and cast products are used in 90% of durable goods, ranging from lamp posts to space shuttles. Still, no casting is perfect. Even with recent innovations in simulation and process technology, nearly every cast product will have some level of imperfection. A clear understanding of casting defects is vital for any casting customer, as it helps guide realistic expectations when working with a casting facility.

While experienced casting facilities are skilled in finding a balance between cost and quality, purchasers should be closely involved in determining admissible levels of defects in deliverable products.

Common Casting Defects

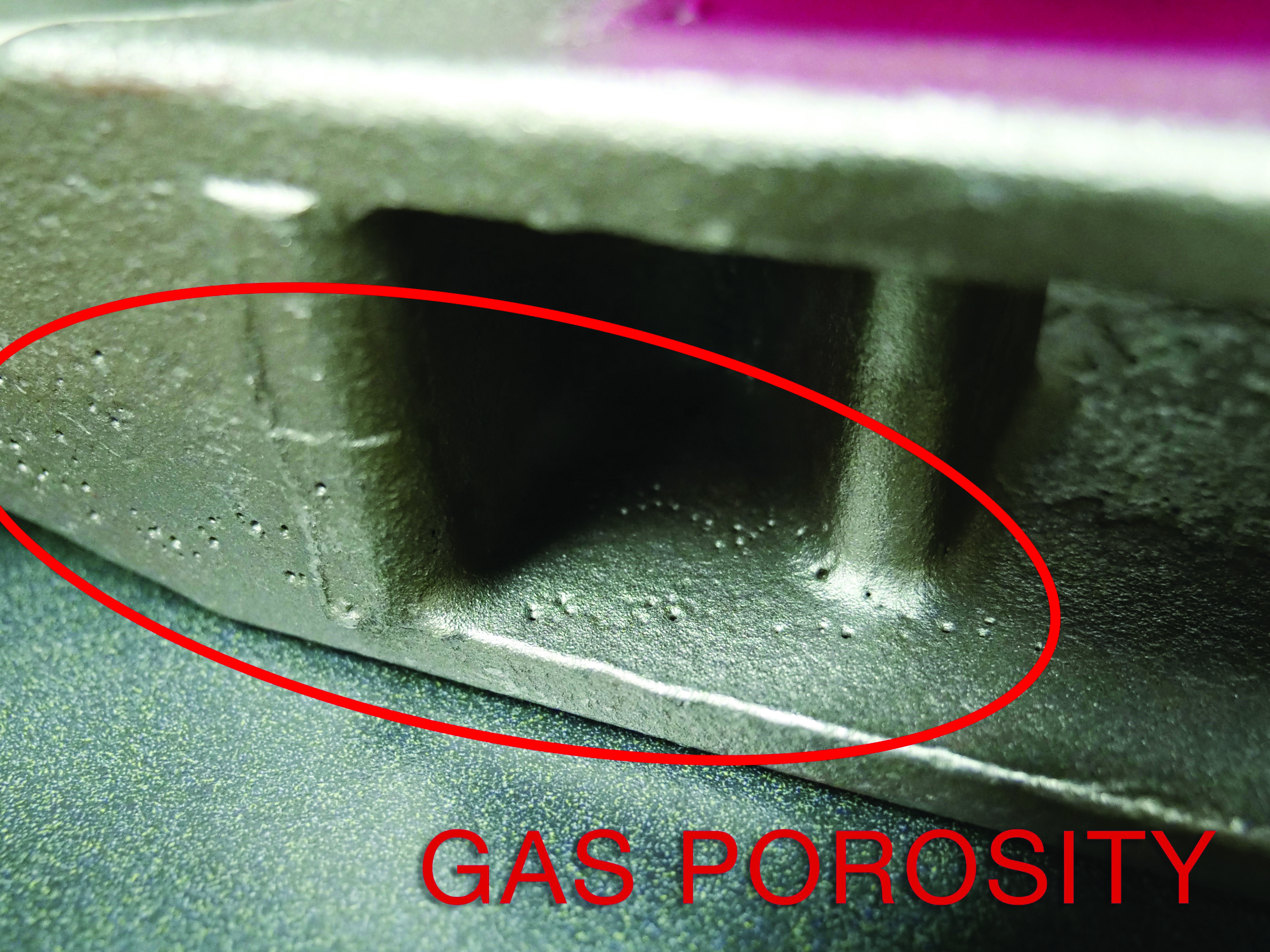

Some of the most common types of casting defects are porosity and inclusions. Porosity can be caused by gas in the alloy, in which case the resulting defects are typically small, negative defects that are elliptical in shape. Porosity can also result from shrinkage, which occurs when insufficient feed material is available in certain areas. In some cases, porosity can even be caused by inclusions or oxides that make their way inside the mold.

Defects that are more often returnable include hot tears, cold lapping, bending, misruns and runout. Hot tears are cracks that form in a casting because of overheated spots in the mold. Cold lapping can occur if pouring temperature or pouring rate is not optimized, and it appears as a division in the casting where one side cooled too much before meeting the other side. Bending can occur in any casting process, but is most common with reusable molds, as in permanent molding. Misruns occur when molten metal fails to fill the mold cavity. This can result from a tilted mold, an insufficient pour or improper pouring temperature.

Particularly in sand casting, runout can also be a common defect. Runout occurs when metal leaks from the mold, caused by a damaged mold or an inadequate seal between the cope and drag.

Preventing or Repairing Casting Defects

If defects result in returns or in-house scrap, casting facilities will adjust workflows to reduce or eliminate their incidence. Melting processes and degassing measures can be adjusted to reduce gas porosity.

Shrinkage porosity can be prevented by designing corners with larger radii, or by optimizing mold and pour temperatures. Inclusions can be reduced by more thoroughly removing slag during melting, or by coating molds so they stay intact until shakeout.

Misruns are often caused by errors in the pouring process and can be corrected through instruction.

Depending on the type, severity, and frequency of casting defects, casting facilities might elect to fix the defects after processing through grinding and welding. Defects that stick up from the surface can be ground away to form a smooth finish.

Porosity from gas or shrinkage–and even misruns in some cases–can be repaired through welding. Welding can restore the part to the same specifications that would have been possible without the defect. Especially after heat treating, cast pieces that have been welded have nearly identical physical properties to fully cast parts.

When a Casting Is Returnable

Determining when a part is returnable is an important aspect of the product development process. Customers and casting facilities need to agree in advance on acceptable levels of defects. For example, any porosity percentage greater than the agreed-upon level will be returnable, but anything less will pass.

Specific characteristics of a part sometimes have different requirements. For example, gas porosity is often invisible until the surface is machined away, revealing defects inside the casting. The customer’s design might require very low levels of porosity in the specific area that will be machined, in order to ensure a smooth surface after machining. As an example, at one investment casting facility interviewed, 99.9% of returns are because of defects discovered through machining.

Other defects might seem to be returnable, but upon closer inspection are not. Small inclusions or shrinkage may produce aesthetic blemishes that customers’ quality control will flag during inspection. However, it benefits both the customer and the foundry to come to an agreement that accommodates a certain level of variability in non-critical surfaces. The cost to completely eliminate aesthetic defects may be too high for the part to be profitable, either for the foundry or the end customer.

Several industry groups offer standard guidelines and ratings systems to help determine admissible levels of defects, including ASTM, ASME and SAE. These standards provide scales to measure the incidence of defects, but every part has different requirements.

Manufacturing processes can be improved and adjusted to bring parts up the scale, but higher quality almost always means higher cost.

In order to ensure a satisfying result for both parties, casting facilities and customers must work together to determine a balance between casting quality, level of defects and overall cost.

Click here to see this story as it appears in the January/February 2020 issue of Casting Source.